A digital representation of a value or a right

7 May 2024

A) Digital representation

At its core, a crypto-asset is a digital representation. While the EU Regulation on Markets in Crypto-assets (MiCA) does not explicitly provide a definition of a “digital representation”, these terms denote the representation of something in the form of digital data – i.e., computerised data or files, similar to an mp3 or a text-file, that are represented using values to embody information (FATF, Virtual Currencies Guidance, p. 36; cf. also: EP, Cryptocurrencies and Blockchain, p. 31).

The array of “things” that can be represented in the form of digital data is vast but can broadly be categorised into two groups: they may either be a representation of “a value” (e.g., they represent the value of an asset) or of “a right” (e.g., they represent the right to access to a good or service). Hence, also under MiCA, crypto-assets may be a digital representation of a value or a digital representation of a right (Recital (2) MiCA; Article 3-1(2) MiCA).

MiCA’s definition of crypto-assets seems however to imply that the representations of “a value” and of “a right” are mutually exclusive; in other words, a digital representation would apparently only qualify as a crypto-asset if it is either a representation of "a value” or, alternatively, a representation of “a right”. Not if it would be both.

However, such is not our interpretation. It is our understanding that the definition aims to clarify that it is sufficient for something to be considered a crypto-asset if it is either a representation of a value or of a right. Thus, something that represents both a "value" and a "right" doubly satisfies the criteria of the crypto-asset definition and may be considered a crypto-asset within the meaning of MiCA, provided that the other conditions are equally met.

As an example, an electronic money token is a type of crypto-asset that represents a value and that purports to maintain stable this value by referencing the value of one official currency, such as euros (Article 3-1(7) MiCA). However, it is also worth clarifying that issuers of electronic money tokens must ensure that holders of such tokens can exercise their right to redeem them at any time, and at par value, against the official currency (Recital (19) MiCA; Recital (67) MiCA; Article 49-4 MiCA; Article 51-6 MiCA; Article 53-2 MiCA). Therefore, it could be argued that an electronic money token represents a value (e.g., €5.-) but also the right to redeem that token (e.g., receive funds, in euros, amounting to €5.-). This does not affect, in any way, its status as a crypto-asset.

Such interpretation would also seem consistent with the intention of MiCA’s crypto-asset definition to capture all types of crypto-assets that currently fall outside the scope of EU legislative acts on financial services (Recital (16) MiCA).

B) Representation of a value

In the vast array of crypto-assets, the majority appears to represent value rather than specific rights. Digital representations of a value include both internal/intrinsic value, and, as it is often the case, external or non-intrinsic value.

Intrinsic value. Generally, an internal or intrinsic value refers to the inherent worth of an asset. This inherent worth of the asset is based on its fundamental characteristics and usefulness. For crypto-assets, the concept of intrinsic value becomes more nuanced. The intrinsic value could be derived from its utility in a specific ecosystem, the technology behind it, or the services it enables. For example, Ether (ETH), the native cryptocurrency of the Ethereum blockchain, could be understood as having some intrinsic value because it is used to pay for transactions and computational services on the Ethereum network.

Perhaps a better example of crypto-assets with intrinsic value are the so-called “stablecoins”. These assets are backed by something and are not just perceived to be “something of value” (EP, Crypto-assets, p. 20). However, MiCA does not define “stablecoins” (Tomczak, Crypto-assets and crypto-assets’ subcategories under MiCA Regulation, p. 376). It rarely uses this term, only referring to stablecoins as assets aiming to maintain a stable value in relation to an official currency, or in relation to one or several assets (Recital (41) MiCA). MiCA also defines and regulates two types of crypto-assets that may be considered stablecoins (MiCA’s Explanatory Memorandum, p. 10; CBI, Markets in Crypto-Assets (MiCA) Regulation; MiCA – the necessary steps for crypto): that is, the ‘asset-referenced token’ and the ‘electronic money token’ (or ‘e-money token’). More on these two types of crypto-assets below.

Another example still of crypto-assets that may have intrinsic value are the so-called “unique and non-fungible crypto-assets”, which are generally referred to as ‘non-fungible tokens’ or ‘NFTs’. These crypto-assets that represent the value of an underlying asset (e.g., digital art or collectibles) do not fall within MiCA’s application scope (Article 2-3 MiCA; Recital (10) MiCA) but are nonetheless referred by it as “crypto-assets”. Furthermore, they fulfil all criteria provided by MiCA’s crypto-asset definition. They may, therefore, be considered crypto-assets and some tokens designated as “unique and non-fungible crypto-assets” may even, in some exceptional circumstances, be governed by MiCA’s provisions – e.g., tokens designated as “non-fungible tokens” minted in a large series or collection (Recital (11) MiCA).

According to MiCA the value of these “unique and non-fungible crypto-assets” (NFTs) is attributable to these crypto-asset’s inherent/internal unique characteristics and to the utility they give to their holder (Recital (10) MiCA). Therefore, these crypto-assets may be considered as having (some) intrinsic value. The same is applicable to crypto-assets representing services or physical assets that are unique and non-fungible, such as product guarantees or real estate (Recital (10) MiCA).

Non-intrinsic value. External or non-intrinsic value refers to the worth of an asset that is not derived from its inherent qualities but rather from external factors such as market demand, speculation, or perceived value. This value is thus arbitrarily attributed to a crypto-asset by the parties concerned, or by market participants (Recital (2) MiCA). This also implies that the value of a crypto-asset can be subjective and that it may be based only on the interest of the purchaser of the crypto-asset (Recital (2) MiCA). This is typically the case of virtual currencies (EP, Virtual currencies and central banks’ monetary policy, p. 7) and, in particular, of the majority of non-backed cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin (EP, Cryptocurrencies and Blockchain, p. 21; BIS, Digital currencies, footnote 2 & end p. 4; Kaplanov, Neardy Money, p. 2).

Despite the non-intrinsic value of some crypto-assets, other crypto-assets falling within MiCA’s application scope seek to stabilise their value by reference to assets. In this regard, MiCA introduces three different types of crypto-assets based on whether or not the crypto-assets seek to stabilise their value by reference to other assets (Recital (18) MiCA).

First type of crypto-assets. The first type of crypto-assets are the ‘electronic money tokens’ or ‘e-money tokens’ (‘EMT’) (Recital (18) MiCA) which consists in a group of crypto-assets that purports to maintain a stable value by referencing to the value of one official currency (Article 3-1(7) MiCA) and only one single official currency (Recital (18) MiCA; Recital (19) MiCA). By official currency, it is meant the official currency of a country, that is issued by a central bank or other monetary authorities – e.g., the €uro (Article 3-1(8) MiCA). The referenced official currency may be the Euro (Article 48-2 MiCA; Article 119-2(k) MiCA; Article 130-4 MiCA), or the official currency of a EU Member State which is not the Euro (Recital 104 MiCA; Article 56-3 MiCA; Article 56-7 MiCA; Article 57-5 MiCA; Article 111-2(d) MiCA; Article 119-2(k) MiCA), or any official currency which is not an official currency of a EU Member State - i.e., GBP or USD (Recital (110) MiCA; Recital (111) MiCA; Article 58-3 MiCA).

By seeking to stabilise the price/value of the token, these types of crypto-assets may contribute to resolve the main shortcoming of other crypto-assets – that is, their high volatility (CE, Impact assessment, p. 28; EP, Crypto-assets, p. 34).

This first type of crypto-assets, together with the second type (presented hereunder), may be considered ‘stablecoins’ (MiCA’s Explanatory Memorandum, p. 10; CBI, Markets in Crypto-Assets (MiCA) Regulation; MiCA – the necessary steps for crypto) which have their value backed by something and which are not just perceived to be “something of value” (EP, Crypto-assets, p. 20).

EMTs are governed by specific rules laid down in Articles 48 to 58 MiCA.

The function of EMTs may be very similar to that of electronic money, as defined in Article 2-2 of Directive 2009/110/EC. Like electronic money, these crypto-assets are (a) electronic surrogates for official currencies, in particular for coins and banknotes (Recital (18) MiCA). Furthermore, like electronic money, such crypto-assets are (b) likely to be used for payments (Recital (18) MiCA), making them “payment tokens”. Finally, both are (c) offered to the public or admitted to trading if the issuer is authorised as a credit institution (a “bank”) or as an electronic money institution within the meaning of Article 2(1) of Directive 2009/110/EC (Recital (19) MiCA; Article 48-1(a) MiCA).

However, up until today, these two assets were also different in some important aspects. Holders of electronic money, contrarily to holders of electronic money tokens, (a) were always provided with a claim on the electronic money institution as a requirement of the provisions currently in force; and (b) had a contractual right to redeem their electronic money, at any moment, against an official currency of a country at par value with that currency (electronic money is “fiat money”) (Recital (66) MiCA).

MiCA aimed to put an end to these differences. After having first excluded 'electronic money' from its scope (Article 2-2(b) Proposal), MiCA now expressly deems ‘e-money tokens’ to be ‘electronic money' (Recital (66) MiCA; Article 48-2 MiCA).

As a result from the above, issuers of EMTs must comply, both, with the relevant operational requirements of electronic money institutions provided by Directive 2009/110/EC (Recital (66) MiCA), and with MiCA's special requirements on issuance and redeemability of e-money tokens (Recital (66) MiCA). With this move, MiCA intends to revolutionise the current status quo (presented by Recital (19) MiCA) and to provide EMT holders with (a) a claim on the issuer of e-money tokens; and (b) a contractual right to redeem it, at any moment and at par value, against an official currency of a country (Recital (19) MiCA; Article 49-4 MiCA).

EMTs might be adopted by users as a means of exchange (Recital (104) MiCA; Recital (110) MiCA), or used for payments (Recital (18) MiCA). However, they are not intended to be used as a store of value (Recital (68) MiCA).

To preserve the value of the first type of crypto-assets (the electronic money tokens), their issuers must have at least 30% of the funds received always deposited in separate accounts in credit institutions (Article 54(a) MiCA) while the remaining funds may be invested in secure, low risk assets that qualify as highly liquid financial instruments with minimal market risk, credit risk and concentration risk (Article 54(b) MiCA).

Second type of crypto-assets. The second type of crypto-assets are the ‘asset-referenced tokens’ (‘ART’) which consists of crypto-assets that are not electronic money tokens and that purport to maintain a stable value by referencing another value or right or a combination thereof, including one or more official currencies (Article 3-1(6) MiCA; Recital (18) MiCA). It may be worth to note that, unlike e-money tokens, which may only maintain a stable value by referencing ‘a value’, ARTs may aim to maintain a stable value by also referencing ‘a right’. This type of crypto-assets covers therefore all other crypto-assets than ‘e-money tokens’ but whose value is typically backed by assets (not by an official currency), so as to avoid circumvention and to make EU Regulation on Markets in Crypto-assets (MiCA) future proof (Recital (18) MiCA). By seeking to stabilise the price/value of the token, it may contribute to resolve the main shortcoming of others crypto-assets – that is, their high volatility (CE, Impact assessment, p. 28; EP, Crypto-assets, p. 34).

There appears to be a misunderstanding regarding ARTs and the final part of its definition, that states "including one or more official currencies". Based on this part, some authors criticised MiCA suggesting that, like EMTs, ARTs would also purport to maintain a stable value by referencing one or more official currencies, which could make some ARTs virtually indistinguishable from EMTs. However, such understanding proceeds from an erroneous reading of the definition: ARTs primarily aim to maintain a stable value by referencing another value or rights than electronic money tokens (therefore, no official currency), and the referencing of such values or rights may then be combined with a reference to other values or rights - which may include one or more official currencies. In other words, if ARTs would come to reference "one or more official currencies", it would only be as a complex token, in combination with another value or right (often assets). By contrast, EMTs purport to maintaining a stable value only by referencing to the value of one single official currency (no assets and no combinations).

ARTs are governed by specific rules laid down in Articles 16 to 47 MiCA.

They might be adopted by users to transfer value or as a means of exchange (Recital (40) MiCA; Recital (56) MiCA; Recital (61) MiCA; Recital (102) MiCA). However, MiCA imposes restrictions on the issuance of ARTs that are used widely as a means of exchange (Article 23 MiCA). ARTs are not intended to be used as a store of value (Recital (58) MiCA).

This second type of crypto-assets, together with the first type (presented above), may be considered ‘stablecoins’ (MiCA’s Explanatory Memorandum, p. 10; CBI, Markets in Crypto-Assets (MiCA) Regulation; MiCA – the necessary steps for crypto) which have their value backed by something and which are not just perceived to be “something of value” (EP, Crypto-assets, p. 20; Recital (41) MiCA).

To preserve the value of the second type of crypto-assets (the asset-referenced tokens), their issuers must have an adequate custody policy for reserve assets (Recital (55) MiCA; Article 37 MiCA), ensure the stabilisation mechanism with appropriate contractual arrangements (Recital (52) MiCA; Article 37 MiCA), ensure that the issuance/redemption of asset-referenced tokens is always matched by a corresponding increase/decrease in the reserve of assets (Article 37-6 MiCA), and have a reserve of assets corresponding at least to the value of tokens in circulation (Recitals (48) MiCA; Recital (54) MiCA; Article 36-7 MiCA).

Third type of crypto-assets. Finally, the third type of crypto-assets are all other crypto-assets that are not ‘asset-referenced tokens’ nor ‘e-money tokens’, which covers a wide variety of crypto-assets, including utility tokens (Recital (18) MiCA). Therefore, this third type is a subsidiary type of crypto-assets that MiCA defines by the negative: whenever a crypto-asset does not fall into any of the other two aforementioned types, it may then fall into this type.

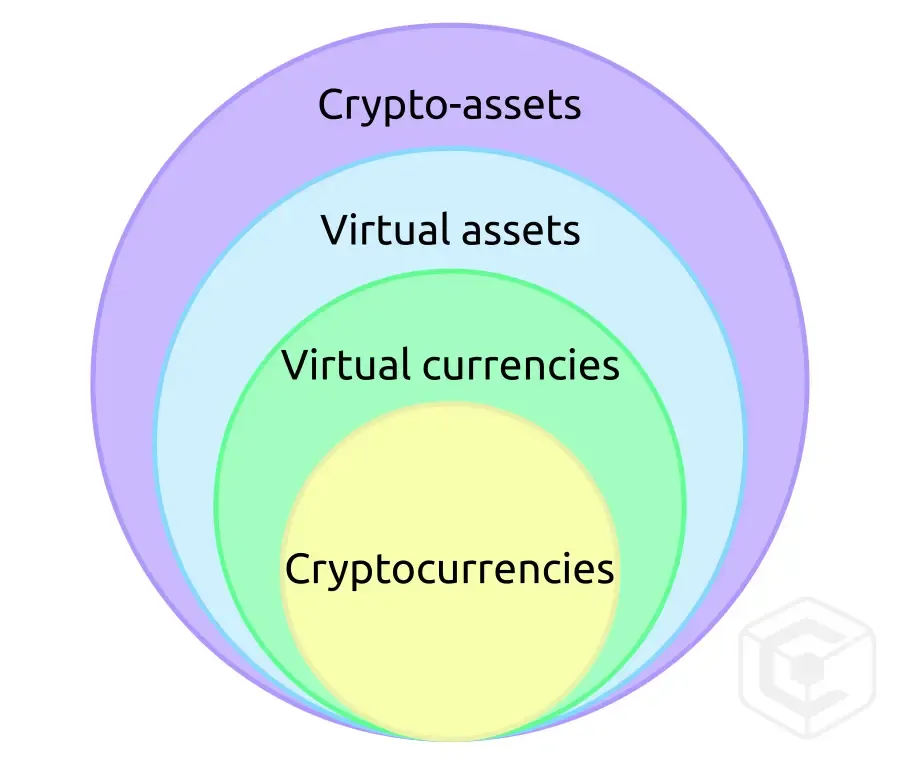

This type of crypto-assets constitutes the so-called catch-all category, that is, a category with a wide spectrum aiming at capturing all types of crypto-assets that currently fall outside the scope of EU legislative acts on financial services, and which may represent value or rights (Recital (16) MiCA). This type of crypto-assets may include other tokens that are neither EMTs nor ARTs, as well as non-backed virtual currencies (Recital (11) AMLR; CE, Impact assessment, p. 5; EP, Crypto-assets, p. 17; EBA, Crypto-assets; OECD, Taxing Virtual Currencies, p. 7; ESMA-EBA-EIOPA, EU financial regulators warn consumers, p. 3). Among these non-backed virtual currencies, we may find the traditional cryptocurrencies, such as Bitcoin, Ether and Ripple. Such cryptocurrencies may be considered crypto-assets (EP, Crypto-assets, p. 18; Tomczak, Crypto-assets and crypto-assets’ subcategories under MiCA Regulation, p. 381; Zetzsche & others, The Markets in Crypto-Assets Regulation (MICA), pp. 6 and 7) and are defined as decentralised convertible ‘virtual currencies’ that are protected by cryptography (FATF, Virtual Currencies Guidance, p. 27 ; EP, Cryptocurrencies and blockchain, p. 21; ECB, Guidance, p. 6; ECB, Impact of digital innovation, p. 12). In other words, cryptocurrencies are a subtype of virtual currencies, which are a subtype of crypto-assets.

This third type of crypto-assets could also include the so-called “unique and non-fungible crypto-assets”, which are commonly referred to as ‘non-fungible tokens’ or ‘NFTs’. These crypto-assets that generally represent the value of an underlying asset (e.g., digital art or collectibles) do not fall within MiCA’s application scope (Article 2-3 MiCA; Recital (10) MiCA) but are nonetheless referred by it as “crypto-assets”. Furthermore, they fulfil all criteria provided by MiCA’s crypto-asset definition. They may, therefore, be considered crypto-assets and some tokens designated as “unique and non-fungible crypto-assets” may even, in some exceptional circumstances, be governed by MiCA’s provisions – e.g., tokens designated as “non-fungible tokens” minted in a large series or collection (Recital (11) MiCA).

C) Representation of a right

Some crypto-assets may represent rights. Crypto-assets that represent rights typically belong to the third type of crypto-assets, that is the catch-all category (more on the three types of crypto-assets above).

Third type of crypto-assets. An example of crypto-assets representing rights and belonging to the third type of crypto-assets are the utility tokens. Unlike NFTs, utility tokens generally do not confer ownership rights (IMF, Virtual assets and Anti-money laundering, p. 6) but are rather crypto-assets only intended to provide access rights to a good or a service supplied by its issuer (Article 3-1(9) MiCA), whether that good or service exists, or does not yet exist, or is not yet in operation (Recital (30) MiCA; Article 4-6 MiCA; Article 12-8 MiCA).

The initial FATF VASP Guidance clarified that it did not exempt specific assets from its obligations only based on their name (e.g., ‘utility tokens’) (FATF, VASP Guidance 2019, §49), but such reference to utility tokens is no longer present in the current FATF Guidance (FATF, VASP Guidance 2021). In fact, the FATF definition of virtual assets (a similar concept to that of crypto-assets) only comprises digital representations of value and not of rights (FATF, VASP Guidance, p. 109). As a result, since utility tokens are digital representations of rights, they are clearly not ‘virtual assets’ under the FATF standards even if they are ‘crypto-assets’ under MiCA (IMF, Virtual assets and Anti-money laundering, p. 6).

In order to ensure a proportionate approach, many MiCA requirements do not apply to utility tokens that provide access to a good or service that exists or is in operation (Recital (26) MiCA; Article 4-3(c) MiCA). They are no less crypto-assets and MiCA explicitly considers them as belonging to the third type of crypto-assets (Recital (18) MiCA).

Some requirements may however apply under MiCA to some utility tokens intended to provide access rights to a good or a service that does not yet exist or that is not yet in operation. MiCA also mentions different types of utility tokens that have fundamentally the same intention: utility tokens that represent (the right to) access to an existing good or service (Recital (26) MiCA; Article 4-3(c) MiCA), utility tokens that represent (the right to) access to a good or service that does not yet exist or is not yet in operation (Recital (30) MiCA; Article 4-6 MiCA; Article 12-8 MiCA), utility tokens that grant its holder the right to collect the good or to use the service (Recital (26) MiCA), utility tokens that grant its holder the right to use it in exchange for goods and services in a limited network of merchants with contractual agreements with the offeror (Recital (26) MiCA; Article 4-3(d) MiCA; Article 6-5(d) MiCA).

Among crypto-assets of the third type that may represent rights we also find the “unique and non-fungible crypto-assets” (NFTs). MiCA seems indeed to explicitly admit that these crypto-assets can represent underlying “assets or rights” (Recital (11) MiCA). In fact, they may only be considered unique and non-fungible crypto-assets if the assets or rights they represent are also unique and non-fungible (Recital (11) MiCA). Usually, these crypto-assets represent the value of an asset and/or ownership rights over that asset (as a certificate of ownership) – including digital art and collectibles (Recital (10) MiCA). As said before, these crypto-assets do not fall within MiCA’s application scope (Article 2-3 MiCA; Recital (10) MiCA) but may be considered as belonging to the third type of crypto-assets. Indeed, MiCA refers to them as “crypto-assets” and they fulfil all criteria provided by MiCA’s crypto-asset definition. Some crypto-assets that are designated as “unique and non-fungible crypto-assets” may even be governed by MiCA’s provisions in some exceptional circumstances – e.g., tokens designated as “non-fungible tokens” minted in a large series or collection (Recital (11) MiCA).

It is worth noting that some crypto-assets do not represent a right, but represent a value while having rights and obligations attached to them (Recital (24) MiCA; Article 6-1(g) MiCA; Article 19-1(d) MiCA; Article 51-1(d) MiCA). Indeed, although almost all crypto-assets constitute a digital representation of value, they also come with a variety of rights (CSSF, CSSF Guidance on Virtual assets). In our understanding, there is no point in operating a distinction between the rights a crypto-asset represents and the rights attached to a crypto-asset: both are ‘rights’ that are intrinsically linked or related to the token and which contribute for its market interest/value.

For example, retail holders that acquired a crypto-asset of the third type (a crypto-asset other than an ART and a EMT) directly from its offeror have generally a withdrawal right during a limited period of time after the crypto-asset acquisition (Recital (37) MiCA; Article 13 MiCA).

First and second type of crypto-assets. Following the previous paragraph, it is worth noting that attached rights mostly concern the other two types of crypto-assets, that is the asset-referenced tokens (ART) and electronic money tokens (EMT).

For example, issuers of EMTs must ensure that holders of such tokens can exercise their right to redeem them at any time, and at par value, against the official currency (Recital (19) MiCA; Recital (67) MiCA; Article 49-4 MiCA; Article 51-6 MiCA; Article 53-2 MiCA). Therefore, it could be argued that an EMT comprises the right to redeem it - a right that is attached to it or that it (also) represents.

On the other hand, the issuer of ARTs must provide a permanent redemption right on ARTs at all times (Recitals (57) MiCA; Article 37-1(c) MiCA; Article 39 MiCA; Article 47 MiCA). In fact, issuers of ARTs must establish a crypto-asset white paper on ARTs that includes information on the rights provided/granted to ARTs holders (Recital (47) MiCA; Article 25-1(c) MiCA).

Lastly, ARTs do not represent a right (they rather represent a value) but may seek to stabilise the value they represent by referencing to rights (Recital (18) MiCA); Article 3-1(6) MiCA).